He doesn’t look like a farmer, and maybe that is because technically, he is not. In fact, if you see my father in passing, you might mistake him for a retired Italian fisherman or even a lost pirate on account of the bright bandanas he often sports. The truth is he straddles a fine line between all of these noble professions. He has devoted his life to the rather obscure art of aquaculture. His specialty: shellfish–specifically oysters.

Growing up, when asked what our parents did at school, I would respond that my father was an oyster famer. This led to an uncomfortable pause from my teacher, and a quick correction: “Henna’s father is a marine biologist. He studies the ocean.” And so, as any smart five year old would do, I kept my mouth shut while my dad was transformed from farmer to scientist before my young eyes.

But I knew the truth. There were no doctoral degrees or lab coats. Sure, he wrote annotated papers, attended aquaculture conferences and had a general insatiable appetite for information regarding his course of work, but, when all was said and done, he harvested the sea in a way conventional farmers harvest the land.

My dad is a bit on the shy side, but get him into an aquaculture setting or out on the open sea and he will light up. He is not much for small talk and cocktail parties (where his finished products end up), but he can talk best feeding practices and oyster breeding conditions for hours. His colleagues were the rougher sort, true seamen at their cores. It wasn’t unusual to hear the swearing of a typical sailor interjected among scientific discourse at his lab. As I a child immersed in that environment, I was more drawn to the forbidden words rather than aquaculture terminology.

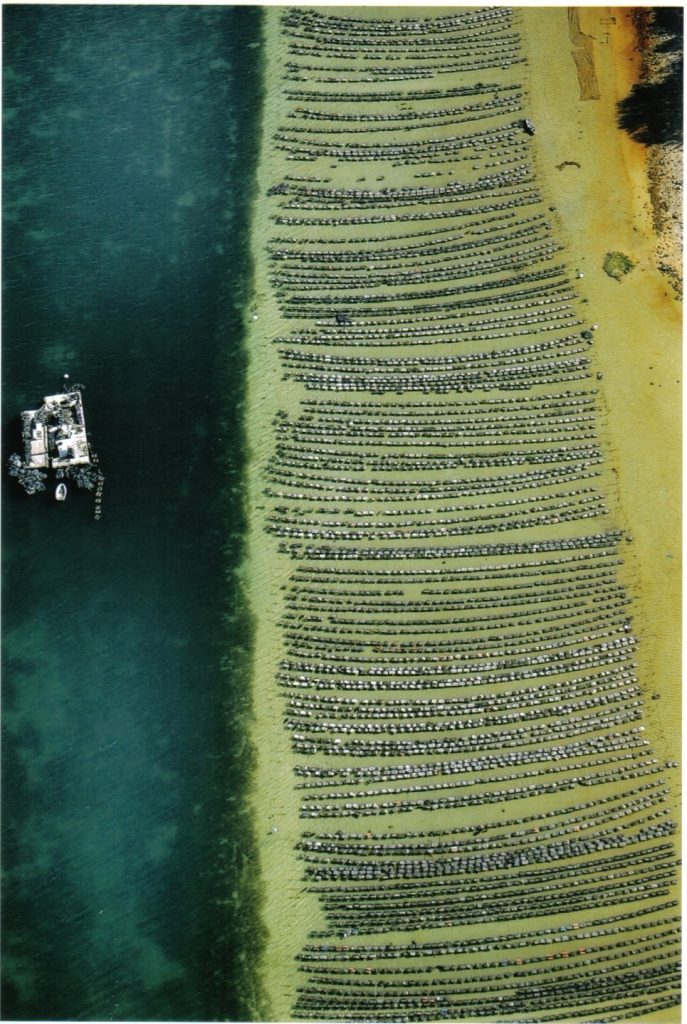

Aquaculture is a strange beast. It is a crossroad where science, manual labor, food and environment meet. Take the oyster for example. It’s romanticized at the table as a sign of a sophisticated palate and a certain measure of wealth. But its background, like many other gourmet foodstuffs, is rather unglamorous. From seed to table, the oyster moves ungracefully from indoor hatchery to small pens in the open water.

The whole process takes about three years, requiring dedication, patience, and physical stamina, as well as precise knowledge to breed and sustain the microscopic offspring. Many oyster farmers buy their seed, eliminating the most fragile stage from production. My dad did not. His prized work was always his hatchery, where inside sterile tanks controlled water-temperature induced the spawning of these hermaphroditic bivalves. The 50 million fertilized eggs that 20 adult oysters might produce are whittled down through their various growth stages. Those lucky enough to survive larvae stages (a million or so) are nourished in the hatchery with algae from glowing green tanks. Eventually, they mature enough to survive on their own inside mesh pens in the ocean.

Oysters are filter feeders, nourishing themselves with the organic outcasts of seawater. Unappetizing as it may seem, their feeding practices make the importance of ocean-based terroir (and an ability to recognize that terroir) crucial in aquaculture. Currents, tides and surrounding waters are all factors affecting growth, survival, and most importantly: taste. Oysters can be salty or sweet, meaty or bland, fishy or delicate, much of this dependent on their growing environment. In fact, they can even be poisonous if their surroundings are too polluted or are exposed to particular bacterial diseases.

My dad’s first farm was on the island of Nantucket, my birthplace and home. He was a pioneer of sorts. In the early 80s aquaculture was still in a trial period globally, and on the island, it was nonexistent. The isolated nature of island living made a great environment for oyster growth and taste, but meant challenges in other areas (small town politics, transportation logistics, bureaucracy).

Hard work for him meant delicious spoils for us. Our summer diet consisted of oysters served raw on the half-shell either plain (lemon and pepper optional) or decadently topped with dab of crème fraiche and black caviar. When the days shortened and cold weather approached, my mom would throw them into a creamy oyster stew or my dad would bake them with spinach, breadcrumbs and butter a la Rockefeller. Not knowing any different, my dad’s oysters were always my favorites.

It wasn’t until my dad abandoned his farm on Nantucket and started consulting on Martha’s Vineyard that I started to pay attention to the subtle nuances of oyster flavor. With new territory came new tastes. By then my dad had colleagues and contemporaries farming up and down the East coast. Boxes of ice-packed oysters would land on our doorstep on the summer: Wellfleet Oysters, Sweet Water, Island Creek, and of course his own masterpieces the Vineyard Tomahawks. Torn open and detached from their protective casings, my dad pointed out the diversity in their shell shape (size, depth, color and sheen) and their meat. We slurped them down, never tainting the pure taste with a metallic fork, but instead using fingers to force the gelatinous fellows down our throats, then greedily slurping up the surrounding briny fluids.

A good oyster should make you thirsty, not for water but rather for more oysters. Some prefer the briny tang that comes with cooler water oysters, while others like the gamey taste of the Pacific breed (typically smaller and less complex in flavor). Some people don’t like the taste at all, and instead of reveling in their delicacy, suffocate any fine distinctions with heavy sauces, a vodka shooter or overwhelming citrus. For me? I prefer my oysters chilled, wet, and fresh: a taste of the ocean, preferably harvested by my dad.